Ancient Persia

The Persian Lion: A Timeless Symbol in Ancient and Modern Iranian Culture

Woven into the rich tapestry of Middle Eastern history, art and symbolism have long conveyed the stories, beliefs, and enduring traditions of ancient civilisations. Central to this heritage is the Persian Lion—an emblem of royal courage, divine authority, and core cultural values. From the rule of Nebuchadnezzar II in Babylon to the peak of the Persian Empire, this lion was far more than a majestic creature; it represented the very essence of civilisation. Yet, the Persian Lion’s legacy does not rest in the distant past. Its influence resonates in contemporary Iran, where it remains a symbol of identity and cultural pride. By exploring the lion’s role across the ages—in monumental architecture, intricate jewellery, ceremonial hunts, and its presence in modern Iran—we discover an enduring connection between humanity, nature, and the cosmos, a link that has persisted for millennia.

Table of Contents

The Persian Lion in Nebuchadnezzar II’s Babylon: A Symbol of Majesty and Power

In the heart of ancient Babylon, under the rule of the ambitious King Nebuchadnezzar II, the Persian lion emerged as a symbol of profound significance. This powerful image, carefully depicted on glazed brick panels, embodied the grandeur and vitality of Nebuchadnezzar’s empire, resonating deeply with the essence of his reign.

Eager to glorify his capital, Nebuchadnezzar commissioned monumental architectural marvels. Vividly hued glazed bricks—drenched in blues, yellows, and whites—became the medium for these masterpieces, reflecting not only divine favour but also the king’s commanding authority. Iconic structures like the Processional Way and the Ishtar Gate illustrated this architectural vision, displaying vibrant designs and colossal scale. Towering above all stood the grand ziggurat, rising seven storeys into the sky, symbolising the zenith of Babylonian splendour.

Yet, amid all this architectural brilliance, the Persian lion held unique symbolic weight. Adorning the walls of the Processional Way and the Palace Throne Room, the lion was far more than mere decoration—it represented Nebuchadnezzar himself, embodying his strength, courage, and unyielding leadership. These majestic lions, roaring in silent defiance, stood as eternal reminders of the king’s indomitable spirit and the enduring power of his empire.

The Persian Lion Hunt: A Grand Ritual of Ancient Monarchs

In the annals of ancient Middle Eastern history, few symbols carry the power and resonance of the Persian lion, often linked with the Asiatic lion. This majestic creature embodied the profound relationship between monarchs and the wild, symbolising the delicate balance between human dominion and nature’s raw force.

The Spiritual Significance of the Persian Lion Hunt

The Persian lion hunt was a ritual imbued with symbolic and spiritual meaning. In ancient civilisations like Persia and Assyria, animals were revered and often considered divine, with the lion seen as a sacred creature bridging the earthly and the divine. When a king embarked on a lion hunt, he undertook more than a physical conquest; he engaged in a ritual of cosmic importance. This act symbolised the king’s alignment with divine forces, reaffirming his god-given right to rule and showcasing his mastery over both the natural and spiritual realms.

The Socio-Political Role of the Lion Hunt

The lion hunt also served as a calculated exercise in political propaganda. Long before mass communication, these grand public displays were among the most effective ways for rulers to project power and authority. A successful hunt showcased the king’s prowess in safeguarding his kingdom, portraying him as a protector capable of conquering any external threat. Just as he subdued the mighty Persian lion, so too could he vanquish the kingdom’s enemies. These events reassured the populace of their ruler’s strength and sent a clear message to rivals about his ability to defend his realm and maintain order.

Ashurnasirpal II: A King Amongst Lion Hunters

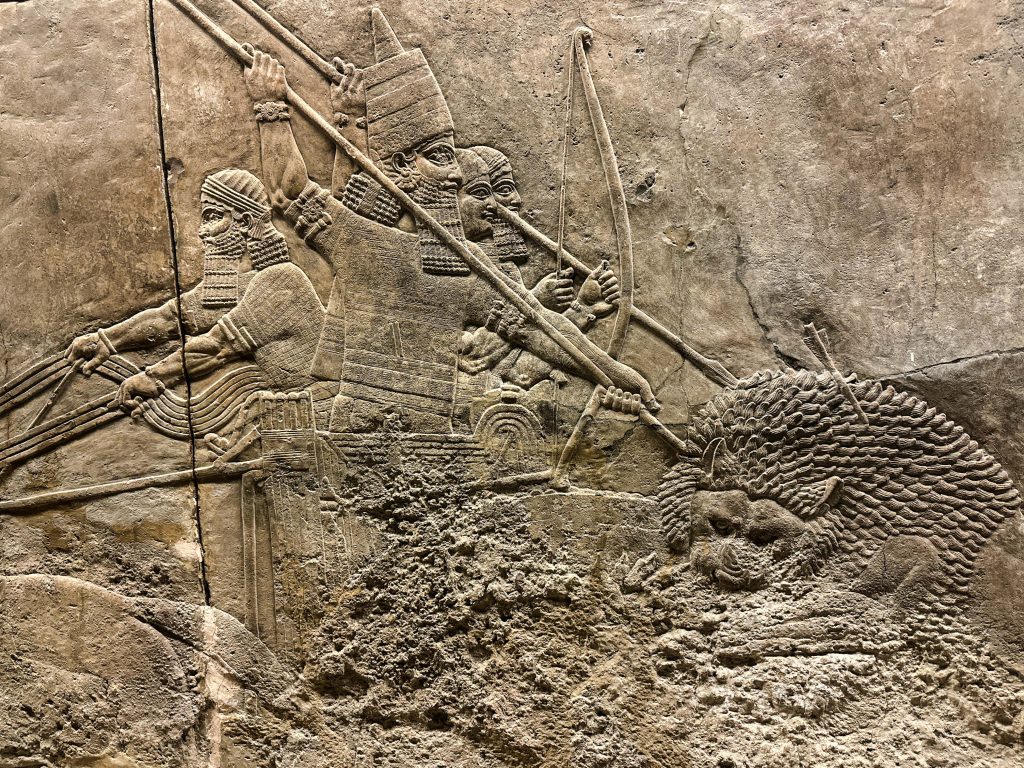

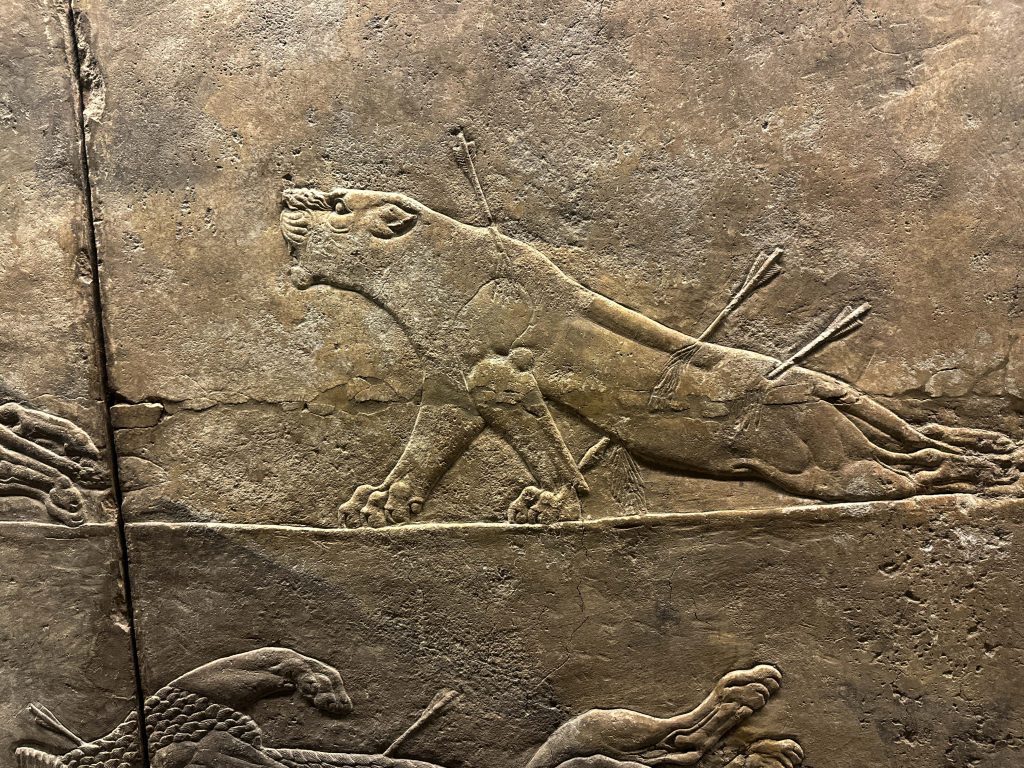

The gypsum wall panel from the North West Palace of Nimrud serves as a remarkable testament to the ancient tradition of lion hunting. King Ashurnasirpal II’s depiction as a skilled and fearless hunter is not merely an artistic embellishment; it reflects historical reality. Ancient inscriptions and texts depict a ruler who took immense pride in his hunting prowess, with bold claims of having killed 450 lions. This was a deliberate public declaration, reinforcing the strength and stability of his reign. For Ashurnasirpal, the lion hunt symbolised his dominance over both nature and his kingdom, embodying his role as protector and supreme leader.

The Persian Lion in Ancient Art: A Plaque from Ziwiye

Among the artefacts that highlight the enduring legacy of the Persian lion is a remarkable piece housed in the Louvre Museum: a quiver plaque depicting a warrior in combat with a lion. This small but intricately crafted object, measuring 4.5 cm by 4.7 cm, is made of gold and dates back to the Iron Age, specifically the 8th century BCE. Discovered in Ziwiye, this artefact offers a glimpse into the artistic and cultural significance of lion hunting during this period.

The plaque likely belonged to a larger decorative set used to adorn a quiver, adding both symbolic and ornamental value. The image of the warrior battling the lion reinforces themes of royal power and bravery, long associated with the Persian lion in Middle Eastern civilisations. This heroic confrontation symbolises the timeless struggle between man and nature, a motif prevalent in the art of this era.

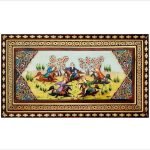

The Continuation of the Persian Lion Hunt in Contemporary Iran: A Legacy in Art

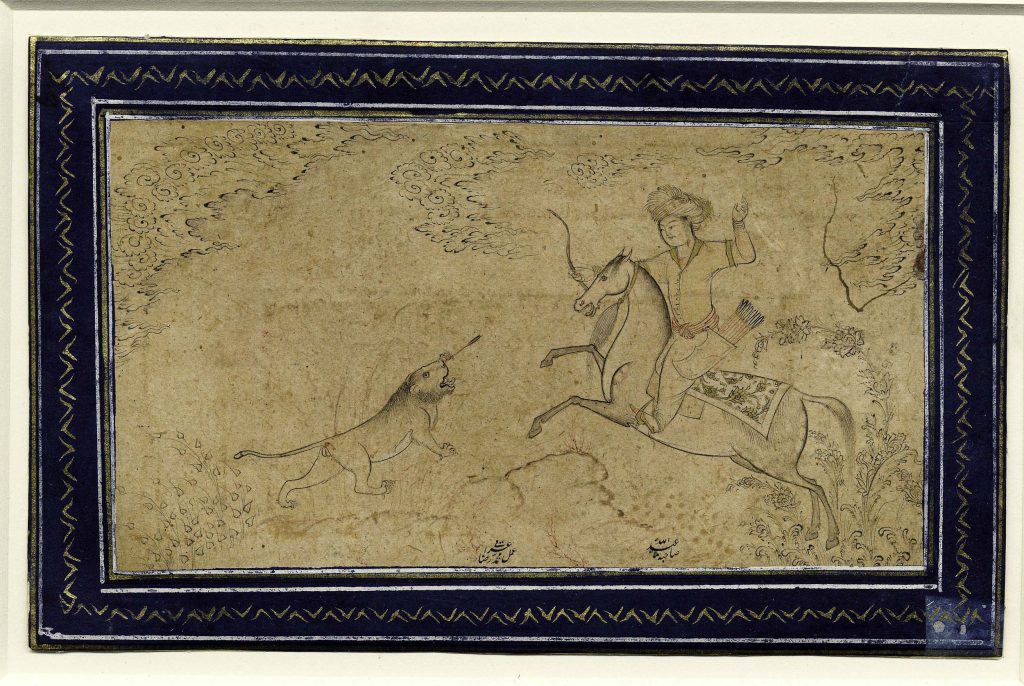

The tradition of the Persian lion hunt, deeply rooted in ancient Middle Eastern civilisations, continued to shape Persian art and culture well into the Safavid era and beyond. A notable example from around 1580 is a Safavid-era drawing in the British Museum, where two hunters on horseback engage a lion, capturing the bravery and skill associated with royal hunts. Executed in ink, gold, and opaque watercolour, the composition reflects the symbolic power of the hunt in Persian culture, representing royal authority and mastery over nature.

Another example from the same period, attributed to Muhammad Riza ‘Iraqi and dated around 1600, also resides in the British Museum. This work from the Isfahan School depicts a horseman shooting an arrow into a lion’s face, further illustrating the enduring theme of man’s triumph over nature. The ornate framing and gilding underscore the hunt as not only a display of power but also an artistic celebration of the ruler’s role as protector and order-bringer.

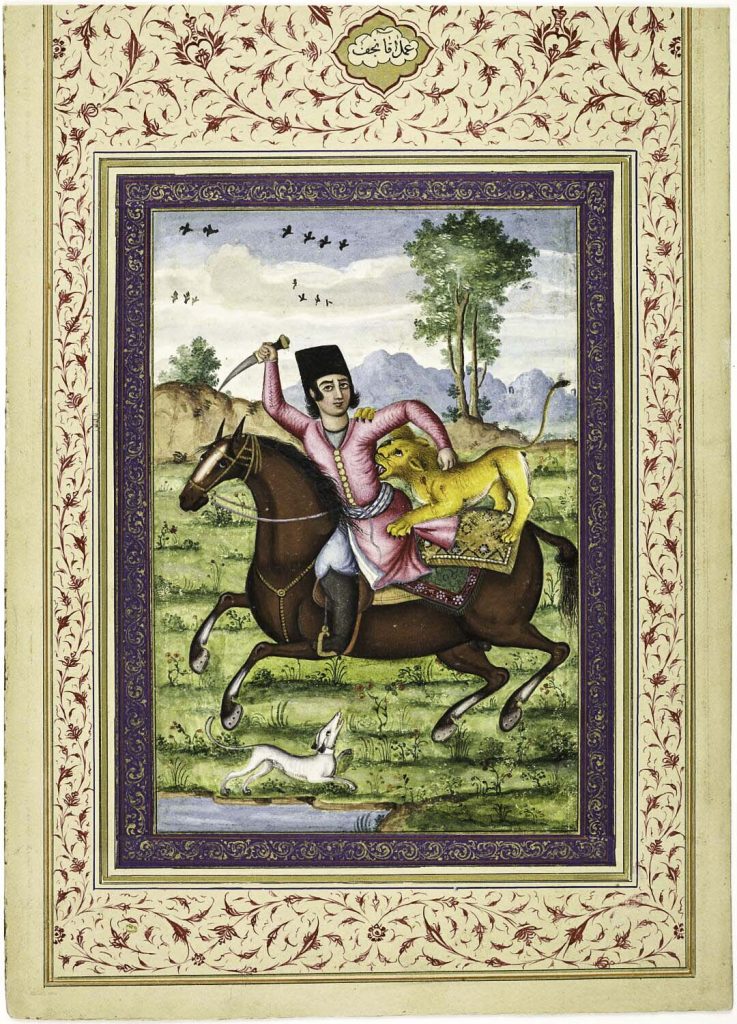

The tradition of the Persian lion hunt endured into the 19th century, as seen in Aqa Nadjaf’s painting Young Man on Horseback Attacked by a Lion, housed in the Louvre. Created between 1825 and 1850, this miniature captures the age-old drama of the hunt, with the horseman struggling to fend off the lion. Although actual lion hunting had declined by this time, its symbolic significance endured in Persian art, representing courage, royal authority, and the eternal struggle between civilisation and the wild.

The Legacy of the Persian Lion Hunt

Although the physical act of hunting the Persian, or Asiatic, lion gradually faded over time, its symbolic power has left a lasting imprint on art, literature, and culture. From ancient sculptures to epic poetry and paintings, the motif of the lion hunt has been repeatedly revisited, capturing humanity’s enduring fascination with the balance of power—both in nature and within the political sphere.

The Persian lion hunt offers a profound glimpse into the soul of ancient Middle Eastern civilisations, revealing the intricate interplay of spirituality, politics, and art that shaped these societies. The dramatic confrontation between the mighty Asiatic lion and the resolute king transcends mere sport, presenting a narrative that, though rooted in antiquity, continues to evoke themes of power, dominance, and the timeless relationship between humanity and nature.

The Return from the Hunt: A Symbolic Journey Back to Civilisation

The grandeur of the Persian lion hunt, with its raw display of courage, dominance, and power, is only part of a larger narrative. Equally significant is the symbolic return from the hunt—a ritualistic transition representing the shift from chaos to order, from the untamed wilderness back to the realm of civilisation.

A Glimpse into the Aftermath

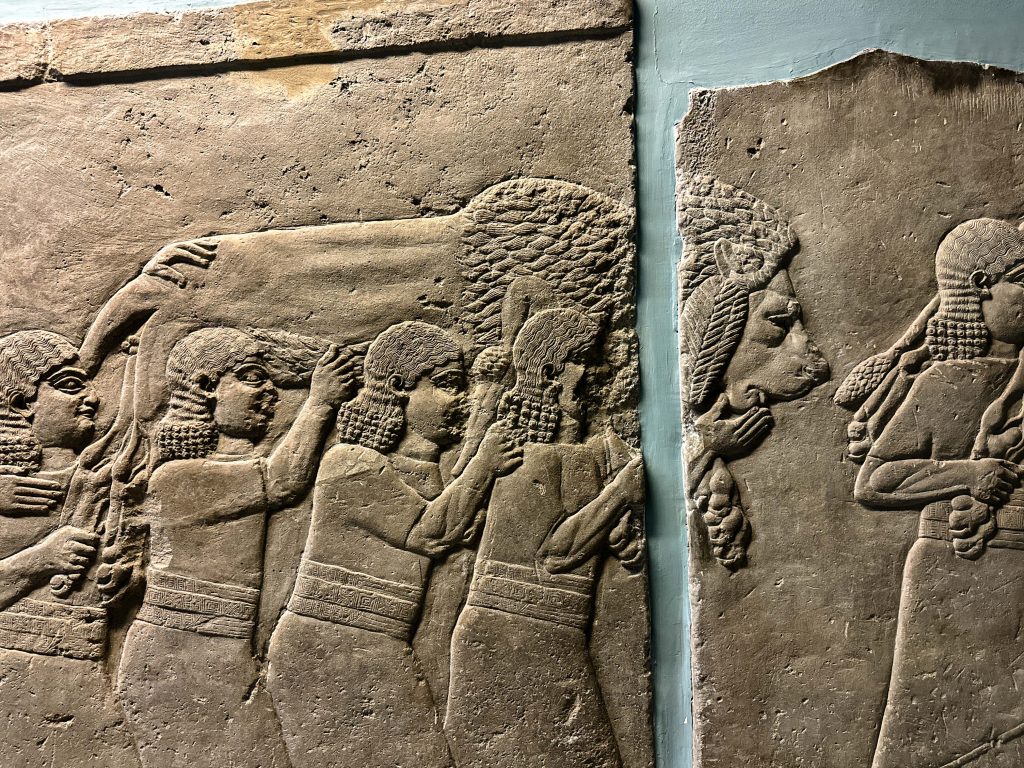

Gypsum wall panels from the North West Palace of Nimrud, dated around 865-860 BCE, vividly portray this return. In these panels, King Ashurnasirpal II is surrounded by bowmen, courtiers, and a fan-bearer, exuding the calm authority of a victorious ruler. In a ceremonial act, the king pours a libation over the body of a slain lion—an evocative symbol of his triumph over the wild. This act underscores the king’s dual role as both conqueror and protector, taming nature’s fiercest creatures and restoring balance.

The scene is enriched by two musicians playing horizontal harps, their music likely adding an atmosphere of solemnity and reverence. The melodies may have echoed both the triumph of the hunt and the sanctity of the ritual, celebrating the king’s divine right to rule. Intricate cuneiform inscriptions accompany the scene, reinforcing the ceremonial importance of the hunt and its aftermath—not merely as a record of events, but as a testament to the deeper spiritual and political significance of these acts.

This return from the hunt, marked by rituals and symbolism, reflects the Assyrian belief in the king’s duty not only to conquer but also to maintain order. The lion, once a symbol of chaos and danger, lies defeated at the king’s feet—a powerful reminder of the monarch’s role as the ultimate civilising force over nature’s wild forces.

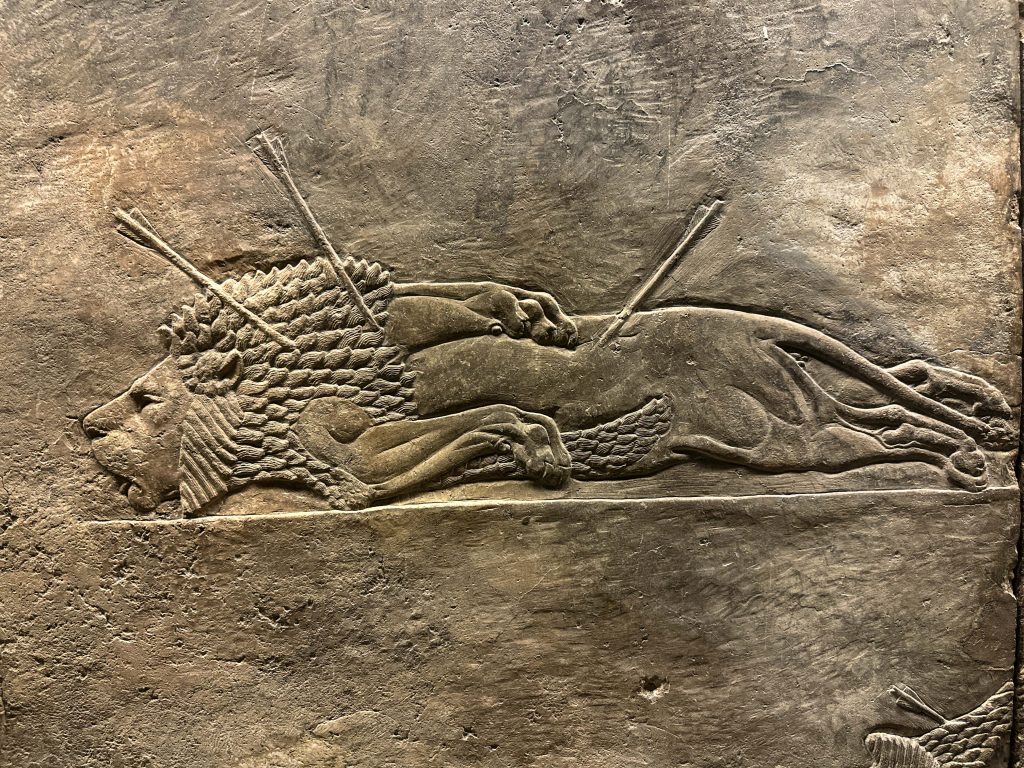

The Spoils of the Lion Hunt

A few decades later, additional panels from the North Palace of Nineveh, dating to around 645-635 BCE, continue the royal lion hunt narrative in striking detail. These meticulously carved panels depict the triumphant aftermath of the hunt, showing men carrying not only the bodies of fallen lions but also an array of other hunted animals, including hares, birds, and even nests. This variety likely symbolises complete mastery over nature, showcasing the king’s dominance over all forms of life, from the ferocious lion to the smallest creatures.

These panels were strategically placed in the corridor leading to the palace’s eastern gate, serving a powerful symbolic purpose. Each time the king returned from a hunt, he would walk through this corridor, surrounded by scenes that reinforced his supreme status as master over both his kingdom and the natural world. The imagery acted as a constant reminder to all who saw it that the king was the ultimate protector, capable of maintaining order and asserting control over the wild forces of nature.

This portrayal of the hunt’s spoils further underscores the lion hunt’s significance in ancient Middle Eastern culture— a ritual that affirmed the king’s divine right to rule. It extended his dominance beyond his realm and into the wilderness itself, symbolising his authority over all realms.

Rituals and Symbolism

The return from the hunt was a deeply symbolic and ritualistic process, representing the restoration of order. Just as King Ashurnasirpal II performed post-hunt rituals, so too did King Ashurbanipal, whose reign is depicted in panels illustrating these essential ceremonial acts. One of the most striking scenes shows the king pouring a libation over the slain lion, a powerful reaffirmation of his role as the divine intermediary between the gods and his people.

The accompanying music, the respectful handling of the hunt’s spoils, and the solemn rituals all contribute to the broader narrative of the hunt—the king’s transition from the chaotic wilderness back to the structured realm of civilisation. Each element, from the libations to the ceremonial return, is laden with meaning, emphasising the king’s ability to bring order out of chaos. Thus, the hunt becomes a metaphor for his divine authority to rule and maintain balance within his kingdom.

| Aspect | Spiritual Significance | Political Significance | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Hunt Itself | King’s alignment with divine forces; sacred ritual | Demonstration of king’s strength and ability to protect | Ashurnasirpal II’s lion hunts |

| Ceremonial Return from Hunt | Restoration of order from chaos; libations over slain lion | Public display reinforcing royal authority | Reliefs showing king pouring libation over lion |

| Display of Spoils | Symbol of dominance over nature and enemies | Propaganda showcasing king’s victories and power | Panels depicting carrying of hunted animals |

| Music and Rituals | Spiritual atmosphere; connection to the divine | Enhancing the grandeur of the event | Musicians playing during ceremonies |

| Artistic Depictions | Eternalizing the ritual’s significance | Reinforcing the king’s image in public memory | Palace reliefs, wall panels |

| Continuation into Later Periods | Preservation of symbolic meanings in art and culture | Legacy of royal authority and tradition | Safavid-era paintings of lion hunts |

In this way, the Persian lion hunt transcends the physical act, becoming a profound statement about power, order, and the king’s sacred responsibility to uphold both, ensuring harmony between the natural and human worlds.

The Persian Lion’s Dominance: A Symbolic Clash in Persepolis

In the renowned city of Persepolis, once the ceremonial capital of the Persian Empire, an evocative artwork commands attention—the exterior walls of the Palace of Darius. From this historical site, a powerful scene captures the Persian lion—potent and fierce—in a gripping confrontation with a rearing bull.

Depicted with a face exuding authority, the Persian lion stands as a powerful representation of the empire’s grandeur and might. Intricate rosette borders, both horizontal and diagonal, surround the majestic creature, reinforcing its dominance in the art and culture of the time.

The choice to feature the Persian lion in such a prominent scene at the Palace of Darius, and its recurrence throughout Persepolis, is hardly accidental. This repeated depiction of the Asiatic lion has led to varied interpretations by scholars. Some suggest that the imagery symbolises an eternal struggle between Good and Evil. Within this context, the Persian lion may represent the god Ahura Mazda from the Zoroastrian tradition, confronting the bull as a manifestation of the evil spirit Ahriman. Another interpretation posits the Persian lion as a symbol of a triumphant king quelling rebels. Additionally, some scholars point to the celestial association of the Asiatic lion with astrology, suggesting that the scene may carry cosmic undertones.

Regardless of the layers of interpretation, one thing is clear: the Persian lion, also known as the Asiatic lion, was far more than a mere animal in the empire’s art—it was a symbol, a narrative, and a powerful emblem of ancient Persia’s grandeur.

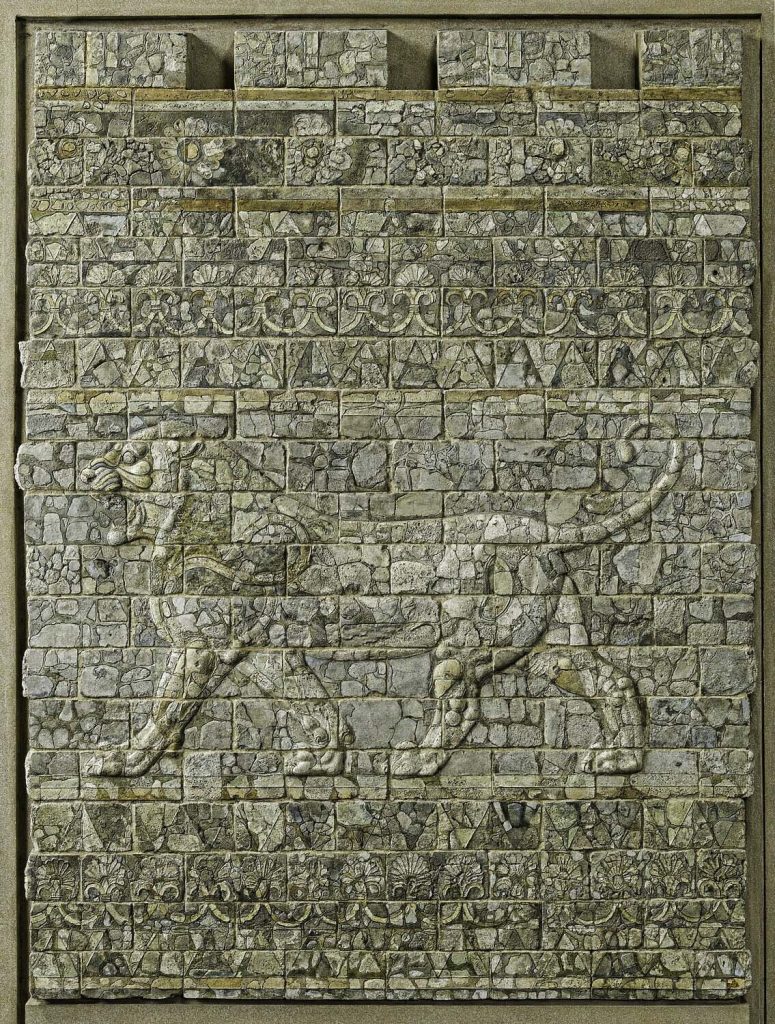

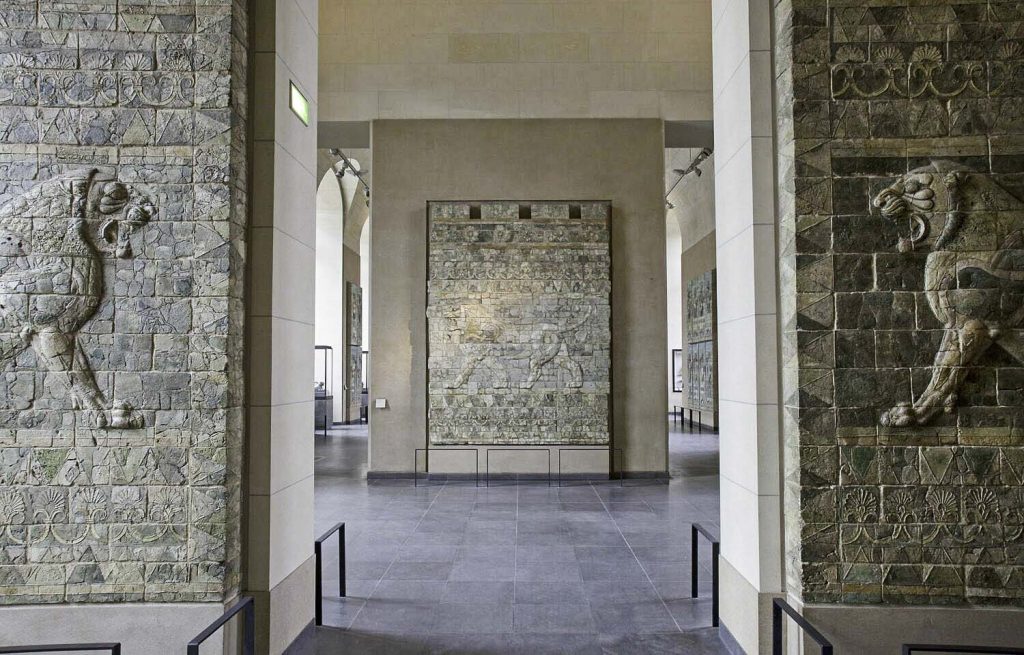

The Lion Frieze of Susa: Symbol of Persian Power and Majesty

In the heart of the Achaemenid Empire, at the Palace of Darius in Susa, a remarkable artwork known as the Frieze of Lions once adorned the palace walls. This monumental glazed brick panel, standing 3.6 metres tall and 2.6 metres wide, depicts a procession of striding lions—majestic and imposing—symbolising the strength and authority of the Persian Empire. Created during the reign of Darius I (522–486 BCE), the lions were crafted from siliceous ceramic with vibrant polychrome glaze, bringing vivid colour and life to this regal imagery.

Discovered in the late 19th century by archaeologist Marcel Dieulafoy, the frieze now resides in the Louvre’s Department of Near Eastern Antiquities. Its detailed, moulded technique and bold colours reflect the Achaemenid emphasis on monumental art that celebrated and reinforced imperial power. The lions, depicted mid-stride, embody the vigilance and might of the Persian rulers, serving as a potent reminder of their dominance.

This frieze not only highlights the artistry of ancient Persian craftsmen but also reinforces the Persian lion’s legacy as a symbol of royal authority. Like the reliefs at Persepolis and other iconic representations, the lions of Susa evoke the grandeur of an empire that projected strength, unity, and stability across its vast territories.

The Persian Lion and Griffins: Gold Emblems of Achaemenid Prestige

In the dazzling courts of the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian lion, alongside the mythical griffin, held a place of prominence, symbolising not only power and strength but also allegiance to the imperial ethos. Their imagery was meticulously curated, intricately woven into the fabric of the empire—both literally and metaphorically.

Exquisitely crafted gold ornaments adorned the robes and headgear of the elite, serving as statements of portable wealth meant to be admired and gazed upon. These adornments amplified the visual spectacle of the court, allowing each courtier to stand out. Yet beyond their allure, these ornaments—especially those featuring the Persian lion and griffin—carried deeper connotations. For satraps, courtiers, or local rulers, wearing such symbols demonstrated allegiance to the central Achaemenid authority, a mark of loyalty to the heart of the empire.

The Persian lion and griffin’s significance was so profound that they were omnipresent in Achaemenid art and architecture. From towering monuments to palace walls echoing tales of valour and grandeur, the Persian lion symbolised pride and power. Its influence extended beyond monumental art, appearing on smaller luxury items—bracelets, textiles, and other jewellery—all bearing the mark of the Persian lion’s enduring prestige.

The Lion Head Applique from Middle Elamite Susa: A Symbol of Ancient Majesty

Dating back to the Middle Elamite period (14th century BCE), this intricate lion head applique, now housed in the Louvre, offers a glimpse into the ancient artistry and symbolism of Khuzistan (Susiana). Crafted in high relief with a diameter of 8.3 cm, the piece features a lion’s head adorned with decorative palmettes and rosettes, embodying the cultural reverence for lions as symbols of power and protection.

The applique is made from bitumen, with bronze and silver accents, and gilded to convey luxury and prominence. The fine detailing and use of precious materials reflect the craftsmanship of the period and the high esteem in which lions were held as emblems of strength and royalty.

Discovered in the region of Susa, this decorative item connects to the broader tradition of the Persian lion as a potent symbol throughout ancient Iranian history. Whether guarding palace walls or adorning objects of art, the lion’s image reinforced the authority and majesty of rulers, a legacy that would resonate through Achaemenid and later Persian art. This applique stands as a reminder of the lion’s enduring presence in Persian iconography, from the Middle Elamite period to the height of the Persian Empire.

The Persian Lion’s Shield: Gilded Glory from Early Sasanian Era

Within the artistic treasury of ancient Iran, the Persian lion remains a symbol of valour, prestige, and cultural exchange. One such artefact, dating back to the 4th century AD—or possibly earlier—is a gilt-silver shield boss that once adorned the centre of a majestic shield, enhancing its defensive and decorative allure.

This remarkable silver-gilt boss exemplifies the intricate craftsmanship of Persian artistry. At its centre is the face of the Persian lion, meticulously detailed and brought to life with masterful touches. While most of the boss shines with the brilliance of silver, select features—the lion’s flowing mane, pronounced cheeks, and regal upper lip—are adorned with a layer of gold applied through mercury gilding, lending it a striking two-toned effect.

The cultural and historical significance of the Persian lion’s depiction on shield bosses extends beyond the Sasanian Empire. A set of Byzantine silver dishes, for example, features allegorical scenes celebrating the biblical tale of David and Goliath, with ‘Goliath’ bearing a shield decorated with a lion head boss that closely resembles this Persian piece. This suggests shared artistic motifs and highlights the Persian lion’s influence across empires.

The Persian Lion in Achaemenid Furniture: A Symbol of Royal Prestige

Amid the artistic expressions of the ancient Achaemenid Empire, the Persian lion stands as a profound emblem of royalty and power. This motif’s splendour is particularly evident in the intricate designs of Achaemenid furniture, where form and symbolism meld seamlessly.

In Achaemenid sculptures, the Persian king is frequently depicted seated majestically on a straight-backed throne. An intrinsic feature of these thrones—and even footstools—was the lion’s paw, meticulously integrated into their legs. Far from a mere decorative choice, the lion’s paw symbolised royalty and dominion. Crafted with exceptional precision, the presence of a bronze lion’s paw also suggests that these thrones were constructed from multiple, intricately detailed sections.

The Achaemenid style’s influence extended beyond the Persian Empire; the lion’s paw motif became fashionable in Egyptian furniture during the Persian period, a testament to the far-reaching influence and admiration of Persian artistry.

Among notable artefacts, a bronze lion-shaped measuring weight offers further insight into the significance of the Persian lion. Inscribed in Assyrian and Aramaic, this weight bears five incised lines on the lion’s flank, denoting the number “five.” Originating from the reign of Shalmaneser V during the Neo-Assyrian period, this artefact, discovered in the North West Palace of Nimrud, Iraq, illustrates the broader Middle Eastern reverence for the lion motif. Whether gracing the throne of a king or etched into the flank of a bronze weight, the Persian lion endures as a timeless symbol of power, prestige, and artistic excellence in ancient history.

Bronze Lion Figurine from Achaemenid Susa: Symbol of Power and Prestige

This bronze figurine of a striding lion, dating to the Achaemenid period (539–330 BCE), exemplifies the enduring symbolism of the Persian lion as an icon of power and majesty. Measuring 5.8 cm in height and 10.8 cm in width, this small yet finely crafted piece likely originated from the Palace of Darius at Susa, although its exact discovery location remains uncertain.

Now housed in the Louvre’s Department of Near Eastern Antiquities, the figurine captures the lion mid-stride—a pose conveying strength, movement, and vigilance. As with other representations from the Achaemenid period, the lion symbolised royal authority and served as a reminder of the king’s protective role over his realm. The choice of bronze, a durable and prestigious material, further emphasises the lion’s role as an emblem of resilience and dominance.

This small but potent object connects to a broader artistic tradition that spans from ancient Elamite and Assyrian depictions to later Persian dynasties. The striding lion motif continued to embody ideals of kingship and Persian cultural reverence for the natural world, symbolising both the lion’s ferocity and the sovereign power of the ruler it represented.

The Persian Lion in the Islamic Era: A Symbolic Continuation

Across the vast tapestry of history, the image of the Persian, or Asiatic, lion endures as a symbol of power, reverence, and nobility. While ancient Persian empires glorified these majestic creatures, associating them with kingship and authority, the reverence for the Persian lion did not fade with time. In the Islamic era, this admiration found renewed expression, seamlessly woven into the evolving fabric of art and culture.

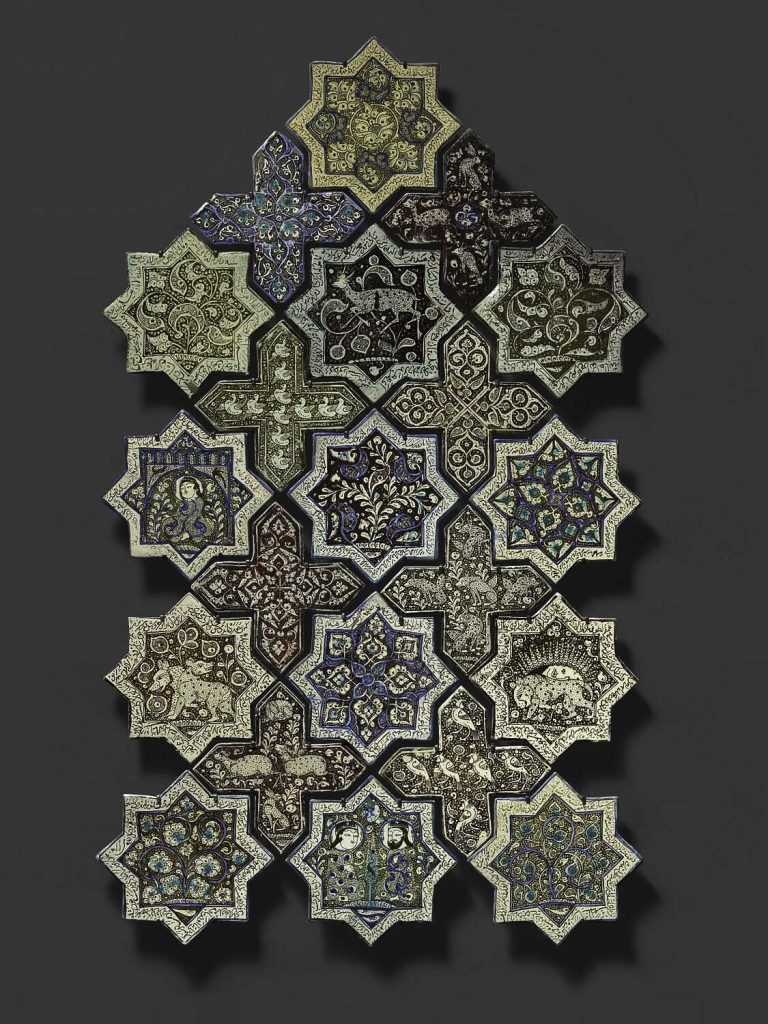

The Lion and Sun Star Tile: A Symbol of Persian Strength and Enlightenment

Among the remarkable artefacts from medieval Iran, the Lion and Sun Star Tile from the 13th century stands as a profound example of Persian symbolism in architecture. This star-shaped ceramic tile, dating to 1266–1267 CE (665 AH), is adorned with the iconic imagery of a lion and sun—motifs long associated with strength, power, and enlightenment in Persian culture. Crafted from siliceous ceramic with a lustrous metallic glaze, the tile measures 20 cm in height and 19.5 cm in width, showcasing exceptional artistry and technical sophistication.

The tile’s decorative elements are enhanced by a border inscription in Naskh script, featuring quatrains of Persian poetry. One verse is attributed to the poet Mahasti Ganjavi, and another to Jalal al-Din Rumi, invoking themes of spiritual transformation, joy, and the transcendent vision of the heart. This poetic addition enriches the symbolic significance of the lion and sun, linking the physical tile to the deeper philosophical and mystical ideas central to Persian literature.

Originally from the Imamzadeh Ja’far mausoleum in Damghan, Iran, this tile is now housed in the Louvre’s Islamic Art Department. It exemplifies the integration of art, poetry, and symbolism in Persian architecture, where objects serve not only as functional or decorative items but as conduits of spiritual and cultural identity. The Lion and Sun Star Tile captures the essence of Persian aesthetics, blending visual splendour with poetic depth to reflect the values and beliefs of its time.

Melding Traditions: Islamic Artistry and the Persian Lion

Islamic visual arts are a rich mosaic of varied influences, embracing calligraphy, geometry, vegetal motifs, and figural representations. While many Islamic artistic elements, such as geometric patterns and plant motifs, drew from the existing Byzantine and Sasanian traditions, the integration of Arabic script as ornamentation was a distinct addition.

A stunning example of this cultural synthesis is a 19th-century steel lion from the Qajar dynasty. This artwork is not merely a representation of the Persian lion; it embodies the diverse artistic elements that define Islamic art. The lion figure, intricately forged from steel, combines figural ornamentation with vegetal designs, creating a visual harmony. Enigmatic scenes of merriment and hunting, with figures dressed in European attire, reflect global influences and interactions of the period. Birds and other animals surrounding the lion emphasise its central significance, while ‘square Kufic’ inscriptions, though undeciphered, add an aura of mystery to the piece.

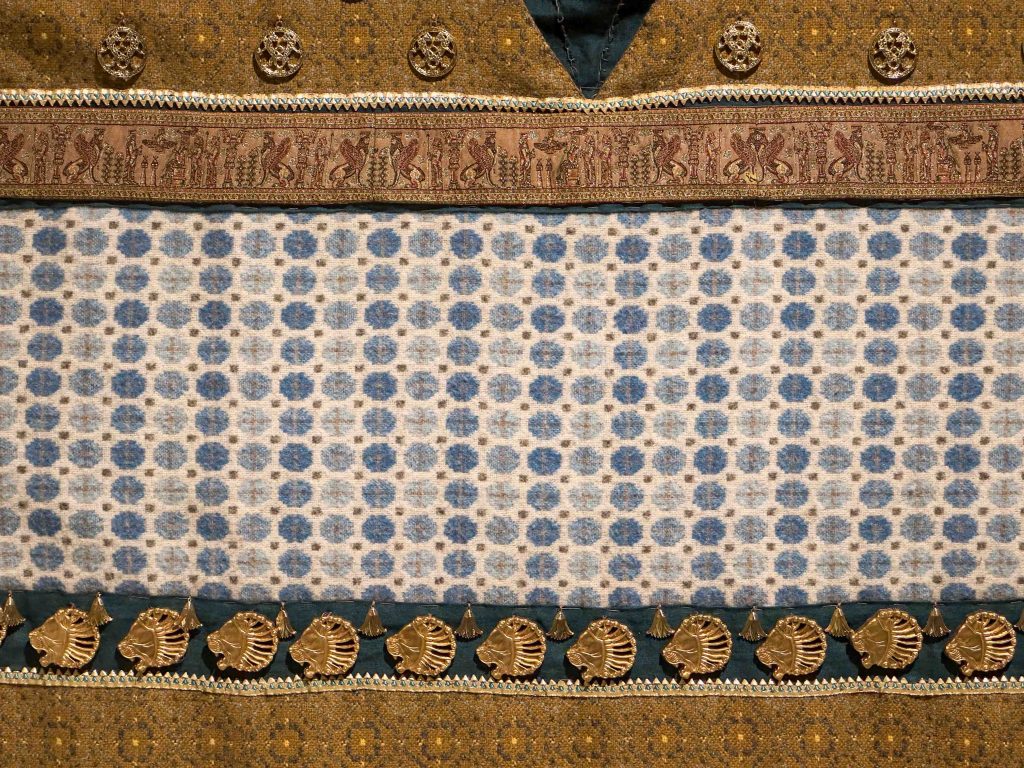

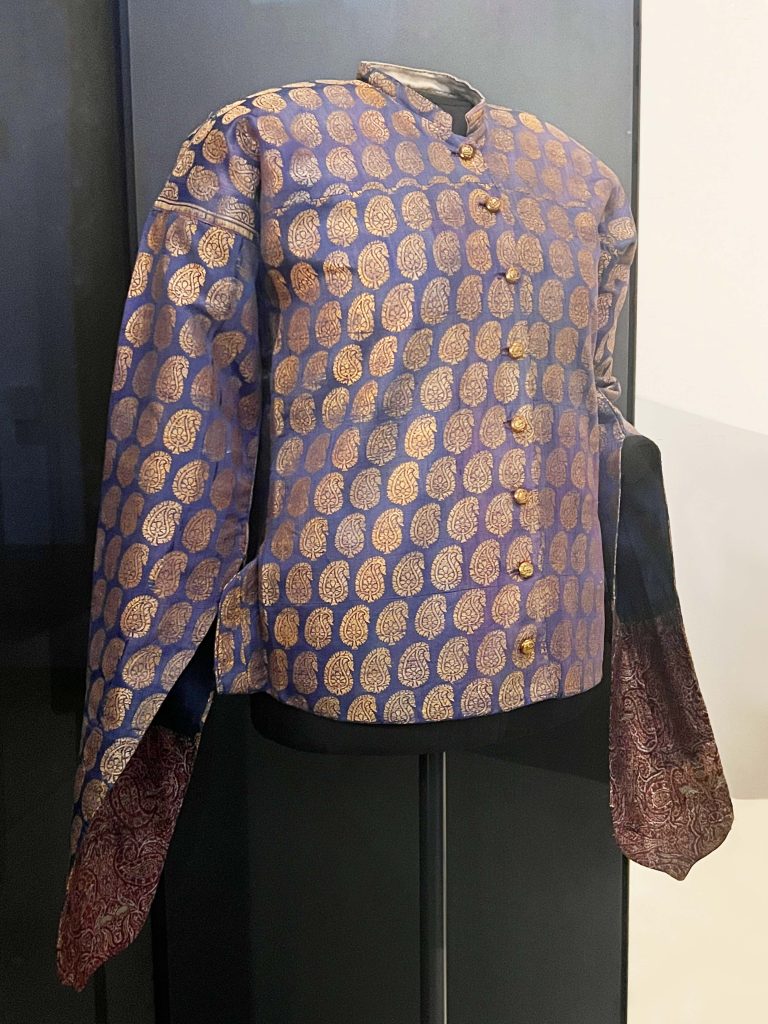

The Persian Lion in Qajar Fashion: A Legacy of Royalty and Power

The Persian lion, an enduring symbol of strength and sovereignty, continued to assert its presence in Qajar-era fashion. A prime example of this legacy is a purple silk brocade jacket from Isfahan, a city renowned for its mastery in Persian arts and crafts. This exquisite garment exemplifies the union of art, symbolism, and status, incorporating the iconic Shir-o-Khorshid (“Lion and Sun”) emblem into Persian royal attire.

Crafted from rich purple silk, the jacket features intricate gold paisley motifs, or boteh—a symbol in Persian art representing life, eternity, and renewal. Against the regal purple background, the shimmering boteh patterns reflect the cultural depth and refinement of the Qajar period. But what truly distinguishes this jacket is its brass buttons, each etched with the iconic Lion and Sun symbol. This emblem, depicting a lion standing proudly beneath a radiant sun, was central to Qajar identity, signifying royal authority, protection, and Iranian sovereignty.

The Shir-o-Khorshid buttons elevate this jacket from clothing to a statement of power and prestige. Worn by nobility, this garment would have silently proclaimed the wearer’s high status, connecting them to a lineage of rulers who adopted the Persian lion as a symbol of strength and legitimacy. In this way, the jacket embodies the continuity of the Persian lion’s symbolism from ancient times to the Qajar era, preserving its association with royal grandeur and cultural pride. More than a piece of fashion, this garment is a woven testament to the lion’s lasting place in Persian identity and the powerful narrative of tradition and sovereignty it represents.

Symbols of National Identity in Modern Iranian Currency: The Lion and Sun Coin and the 10 Rial Banknote

In modern Iranian currency, national symbols have played a vital role in reflecting and preserving the country’s rich cultural heritage. A notable example is the 10 rial silver coin minted in 1965 (AH 1344) under the rule of Muhammad Reza Shah. This coin features the iconic Lion and Sun emblem on its obverse—a symbol deeply rooted in Persian history, representing strength, resilience, and national identity for centuries. Initially tied to royal authority and later adopted as a broader national symbol, the Lion and Sun motif underscores the continuity of Iran’s heritage from ancient times to the modern era. Crafted from silver, the coin links the monarchy of Muhammad Reza Shah to a legacy spanning millennia, serving as a testament to the enduring symbolism of the Persian lion and its evolution as an emblem of both political authority and Iranian pride.

Similarly, the 10 rial banknote issued by Bank Melli Iran in 1934 reflects a similar emphasis on national identity during Iran’s modernisation under Reza Shah Pahlavi. Measuring 125 mm by 65 mm, this banknote was more than currency—it represented Iran’s efforts to assert its cultural identity and independence through a modern banking system. The inclusion of national symbols reinforced a sense of pride and connection to Iran’s historical legacy, positioning currency as a tool for promoting cultural continuity. Issued by Bank Melli, a pivotal institution in bolstering Iran’s economic autonomy, this banknote highlights the role of currency in symbolising the nation’s aspirations for sovereignty and self-reliance.

Together, these artefacts demonstrate how Iran’s modern monetary system has used currency design to reflect and preserve its cultural heritage. Whether through the Lion and Sun emblem on a silver coin or the symbolic designs on a banknote, Iranian currency serves as a bridge between the country’s storied past and its vision for the future.

Conclusion

The Persian lion has endured as a symbol of power, majesty, and cultural identity across the shifting tides of Iranian history. From the ancient empires to the Islamic period and into modern times, this iconic figure has woven through Persian art, architecture, and everyday objects, adapting its form yet retaining its profound symbolic weight. Whether depicted in grand monuments, woven into the royal attire of the Qajar court, or engraved on coins and banknotes, the Persian lion consistently embodies strength, resilience, and the unbroken continuity of Iranian heritage.

| Context | Symbolism | Explanation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Authority | Strength, courage, divine right to rule | Lion represents the king’s power and his god-given authority over the land and people | Lion hunt reliefs, throne decorations |

| Spiritual Significance | Bridge between earthly and divine realms | Lion as a sacred creature involved in rituals aligning the king with divine forces | Ritual lion hunts, libation scenes after hunts |

| Cosmic Struggle | Battle between good and evil, cosmic balance | Depictions of lion attacking bull symbolising cosmic events or zodiac interpretations | Reliefs at Persepolis |

| National Identity | Cultural pride and sovereignty | Lion used as a national emblem representing Iran’s heritage and unity | Lion and Sun emblem on coins and flags |

| Artistic Motif in Islamic Art | Integration with Islamic symbolism | Lion imagery combined with Islamic art elements like calligraphy and geometric patterns | Lion and Sun Star Tile, Qajar-era artworks |

| Political Propaganda | Projection of power and protection | Public displays of lion hunts to showcase the king’s ability to protect and lead | Grand lion hunt ceremonies, monumental art |

Throughout each era, the lion’s image has served more than an ornamental purpose. In the Achaemenid, Sasanian, and Qajar periods, its presence on thrones, weapons, and garments asserted royal authority and sovereignty, grounding rulers in a legacy of power and protection. Under Islamic rule, the Persian lion found new life in poetry, decorative art, and spiritual symbolism, demonstrating how cultural motifs can transcend religious and political changes. In the modern era, national currency, monuments, and even fashion have preserved the Persian lion’s emblematic legacy, bridging Iran’s storied past with its evolving identity.

Today, the Persian lion remains a powerful testament to Iran’s cultural pride and resilience. Its image links ancient Persia’s legacy with the country’s contemporary aspirations, embodying a narrative of continuity that celebrates the enduring values of honour, sovereignty, and identity. Through each adaptation, the Persian lion serves as a potent reminder of the strength and unity that have shaped Iranian culture and continue to inspire it today.

About Craftestan

Experience the timeless beauty of Persia with Craftestan, a haven where ancient tales and refined Persian artistry come to life. Dive into Craftestan’s universe, an ode to the ageless elegance and master craftsmanship that have defined Persian traditions for centuries.

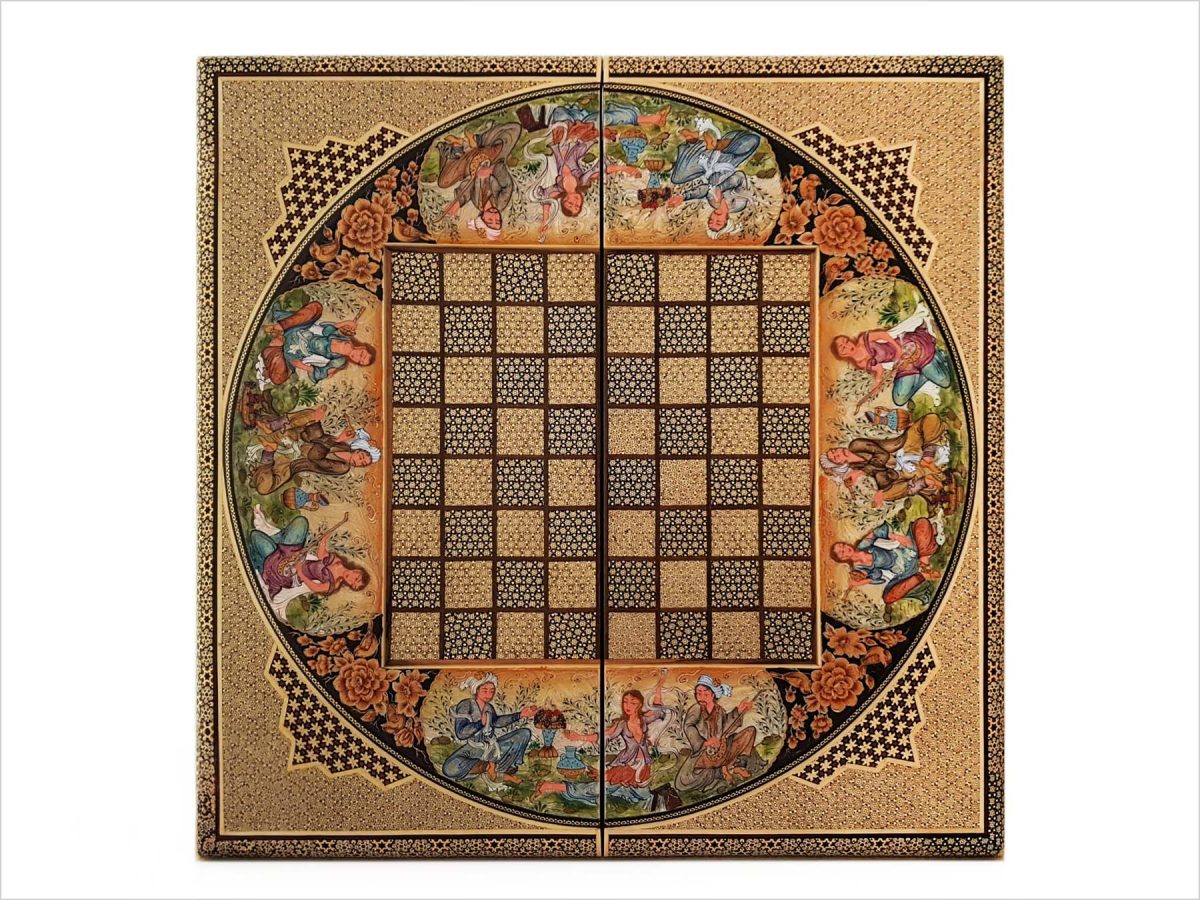

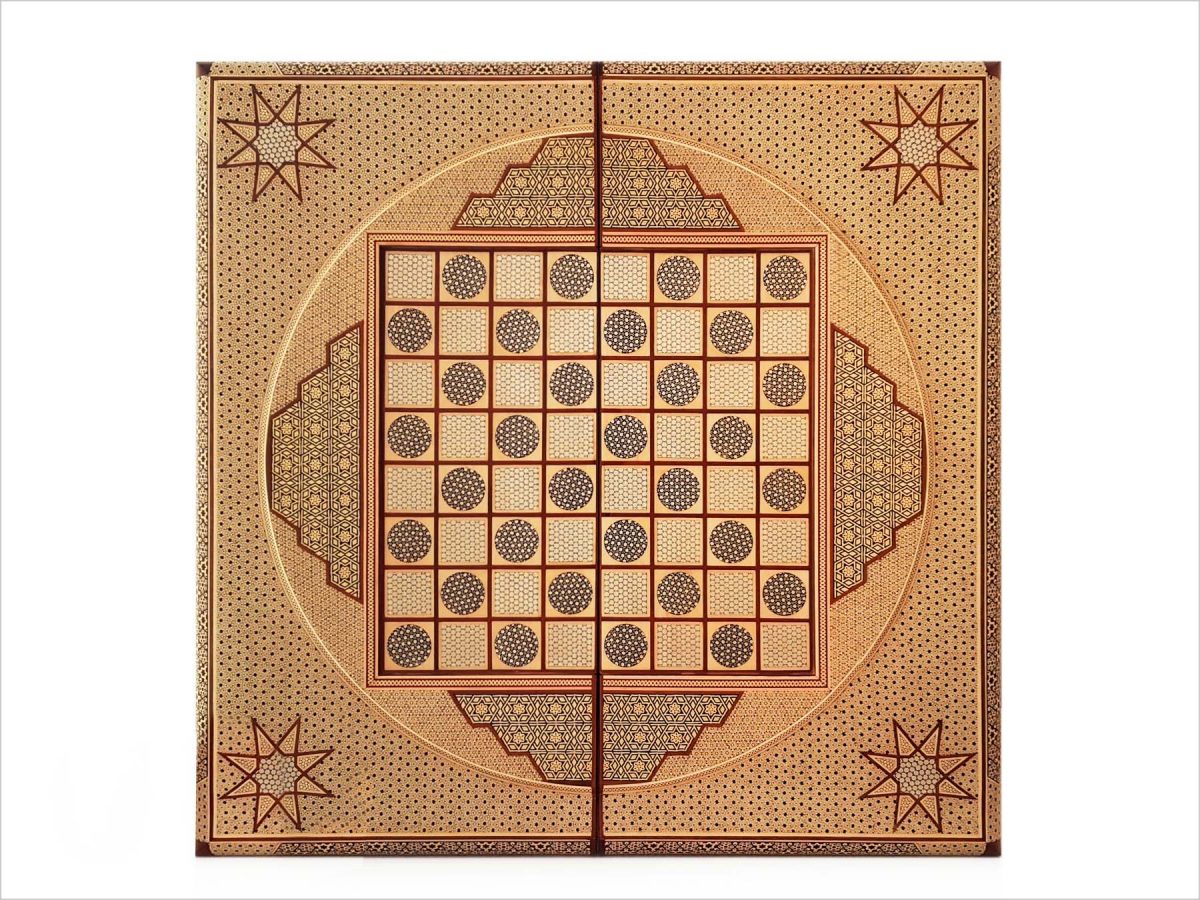

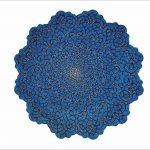

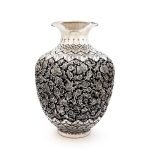

More than a mere marketplace, Craftestan is a vibrant tapestry of Persian culture’s enduring charm. Here, you can discover and treasure artisanal pieces, each echoing the majestic tales and unparalleled craftsmanship of yesteryear Persia. Revel in the allure of Persian enamel or Minakari, admire the meticulous stitches of Persian embroidery or Souzan Doozi such as Pateh and Termeh, or lose yourself in the elaborate patterns of Persian marquetry or Khatam Kari. Every crafted item is a harmonious blend of history and sophistication.

Venturing into Craftestan means forming a bond with the narratives and the artisans who’ve devotedly sculpted each masterpiece, channeling age-old skills inherited from their forebears. Whether you’re drawn to the vibrant hues of Persian turquoise or Firouze Koubi or the delicate intricacy of Persian filigree or Malileh Kari, you’re beholding a slice of Persian art’s essence and innovation.

At its core, Craftestan champions empowerment and preservation. Our aim transcends celebrating Persian cultural gems; it’s about uplifting, notably the talented and tenacious women artisans of Iran. We offer them a platform to share their visions, turning their creations into beacons of hope and symbols of transformative change within their circles.

Acquiring a Craftestan creation isn’t just about possession; it’s about endorsing a storied heritage, championing the profound artistic streams, and aiding in the resurgence of ancient Persian techniques like Persian touristic or Ghalam Zani. By aligning with us, you amplify the voices of these craftsmen and craftswomen, empowering them to revitalize their communities through art.

We cordially beckon you to immerse yourself in Craftestan’s captivating narratives and the mesmerising realm of Persian artistry. May every item you select whisk you away to an era of Persian opulence, instilling a sense of unparalleled cultural depth and elegance in your spirit.

FQAs

What is the significance of the Persian lion in ancient Persian culture, particularly during Nebuchadnezzar II’s Babylon?

The Persian lion was a powerful symbol of strength, courage, and royal authority in ancient Persian culture. During Nebuchadnezzar II’s reign in Babylon, the lion was prominently featured in art and architecture, such as on the glazed brick panels of the Processional Way and the Ishtar Gate. These vibrant depictions were more than decorative elements; they embodied the king himself, representing his indomitable spirit and the grandeur of his empire. The lion served as an eternal reminder of Nebuchadnezzar’s commanding presence and the divine favour bestowed upon his rule.

How did the Persian lion hunt serve both spiritual and political purposes in ancient Middle Eastern societies?

The Persian lion hunt was a ritual of immense symbolic and spiritual importance. Spiritually, it was seen as the king’s alignment with divine forces, reaffirming his god-given right to rule and showcasing his mastery over both the natural and spiritual realms. Politically, the hunt acted as a form of propaganda, projecting the king’s power and authority. By successfully hunting the lion—a creature considered both sacred and formidable—the king demonstrated his ability to protect his kingdom and conquer any threat, thereby reassuring his subjects and intimidating potential rivals.

In what ways has the depiction of the Persian lion evolved in art from ancient times to modern Iran?

The depiction of the Persian lion has evolved while retaining its core symbolism of power and authority. In ancient times, it appeared in monumental architecture and intricate artefacts, like the reliefs of Persepolis and the gold quiver plaque from Ziwiye, symbolising royal power and bravery. During the Islamic era, the lion motif was integrated into Islamic art, as seen in the 13th-century Lion and Sun Star Tile, which combined traditional Persian symbols with Islamic artistic elements. In modern Iran, the lion continues to be a national symbol, appearing in Qajar-era artworks, fashion, and even currency, such as the Lion and Sun emblem on coins and banknotes, reflecting enduring cultural pride and identity.

What is the historical and cultural significance of the Lion and Sun emblem in Iranian society?

The Lion and Sun emblem is a deeply rooted symbol in Iranian culture, representing strength, resilience, and national identity. Historically, it was associated with royal authority and later adopted as a broader national symbol. The lion symbolises courage and power, while the sun represents enlightenment and divinity. This emblem has been used in various forms, from architectural tiles and royal attire in the Qajar era to modern currency like the 1965 10 rial silver coin. Its continued presence underscores the enduring importance of the Persian lion in expressing Iran’s cultural heritage and sovereignty.

How does the Persian lion symbolise the connection between humanity, nature, and the cosmos in Iranian culture?

The Persian lion embodies the intricate relationship between humanity, nature, and the cosmos by symbolising strength, divine authority, and the balance of power. Ancient rituals like the lion hunt were not just physical conquests but spiritual ceremonies that signified the king’s cosmic role and his alignment with divine forces. Artistic depictions, such as the lion attacking the bull in Persepolis, have been interpreted as representations of cosmic struggles or celestial events, linking earthly authority with the movements of the heavens. Through these rituals and artworks, the Persian lion serves as a metaphor for humanity’s place within the natural world and the larger cosmic order, a theme that has persisted throughout millennia in Iranian culture.

| Time Period | Culture/Empire | Role of the Persian Lion | Examples/Artefacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6th century BCE | Babylon under Nebuchadnezzar II | Symbol of royal power and majesty | Glazed brick panels on the Processional Way and Ishtar Gate |

| 9th century BCE | Assyrian Empire | Representation of the king’s strength and divine right to rule | Lion hunt reliefs of King Ashurnasirpal II |

| 8th century BCE | Ancient Persia | Emblem of bravery and royal authority | Gold quiver plaque from Ziwiye |

| 6th–4th century BCE | Achaemenid Empire | Symbol of imperial power and cosmic struggle | Reliefs of Persepolis depicting lion attacking bull |

| 3rd century CE–7th century CE | Sasanian Empire | Icon of royal prestige and craftsmanship | Gilt-silver shield boss with lion head |

| 13th century CE | Islamic Persia | Integration of lion symbolism with Islamic art | Lion and Sun Star Tile from Damghan |

| 19th century CE | Qajar Dynasty | National symbol reflecting royal authority and cultural identity | Purple silk brocade jacket with Lion and Sun buttons |

| Modern Era | Iran | Emblem of national identity and cultural heritage | Lion and Sun on coins and banknotes |

Reference List

Amélie Kuhrt (2010). The Persian Empire : a Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. London: Routledge.

Briant, P. (2002). Cyrus to Alexander : a History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns.

Brosius, M. (2006). The Persians. Routledge.

Curtis, J. (2020). Studies in Ancient Persia and the Achaemenid Period. BOD – Books on Demand.

Fergus Millar (2006). A Greek Roman Empire : Power and Belief under Theodosius II (408/450). Berkeley: University Of California Press.

Holland, T. and Folio (2018). Persian Fire : the World Empire and the Battle for the West. London: The Folio Society.

John Gibson Warry (2005). Alexander, 334-323 BC : Conquest of the Persian Empire. Westport, Conn.: Praeger.

Millar, F. (2011). Rome, the Greek World, and the East. Univ of North Carolina Press.

Morgan, J. (2017). Greek Perspectives on the Achaemenid Empire : Persia through the Looking Glass. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Zeinert, K. (1997). The Persian Empire. Tarrytown, N.Y.: Benchmark Books.

Oil Painting

Oil Painting Miniature Painting

Miniature Painting Wall Ornaments

Wall Ornaments Enamel

Enamel Filigree

Filigree Turquoise

Turquoise Decorative Plate

Decorative Plate Home Accents

Home Accents Decorative Vase

Decorative Vase Pāteh

Pāteh Térméh

Térméh Home Accents

Home Accents Mirror

Mirror Tea ware & Tea

Tea ware & Tea Backgammon / Chess Board

Backgammon / Chess Board Home Accents

Home Accents Office

Office Wall Clock

Wall Clock Home Accents

Home Accents Vase

Vase Decorative Vase

Decorative Vase Wall Decor

Wall Decor Home Accents

Home Accents Mirror

Mirror Vase

Vase Embroidery

Embroidery Enamel

Enamel Marquetry

Marquetry Watercolour Painting

Watercolour Painting Under £20

Under £20 Under £50

Under £50 Under £100

Under £100 Under £200

Under £200 Under £300

Under £300 Mother’s Day

Mother’s Day Anniversary

Anniversary Her

Her Him

Him Ancient Persia

Ancient Persia Persian Artefacts

Persian Artefacts Persian Clothing

Persian Clothing Persian Gift Ideas

Persian Gift Ideas Oil Painting

Oil Painting

“This is exactly what I was looking for, thank you!”

“This article is really informative and well-written!”

“Your writing style is engaging and clear, love it!”

“Amazing post, keep up the good work!”

Your writing is a true testament to your expertise and dedication to your craft. I’m continually impressed by the depth of your knowledge and the clarity of your explanations. Keep up the phenomenal work!

You’re so awesome! I don’t believe I have read a single thing like that before. So great to find someone with some original thoughts on this topic. Really.. thank you for starting this up. This website is something that is needed on the internet, someone with a little originality!

This is my first time pay a quick visit at here and i am really happy to read everthing at one place

I simply could not go away your web site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the standard info a person supply on your guests Is going to be back incessantly to investigate crosscheck new posts

The degree to which I appreciate your creations is equal to your own sentiment. Your sketch is tasteful, and the authored material is stylish. Yet, you seem uneasy about the prospect of embarking on something that may cause unease. I agree that you’ll be able to address this matter efficiently.

Thank you for your kind words and thoughtful feedback. I’m glad you appreciate the content and style. Your encouragement gives me confidence to tackle challenging topics in the future.

What a fantastic resource! The articles are meticulously crafted, offering a perfect balance of depth and accessibility. I always walk away having gained new understanding. My sincere appreciation to the team behind this outstanding website.

Thank you for your heartfelt appreciation! I’m thrilled to hear that you find the articles both insightful and accessible. Your support motivates us to keep delivering quality content.

I genuinely enjoyed the work you’ve put in here. The outline is refined, your written content stylish, yet you appear to have obtained some apprehension regarding what you wish to deliver thereafter. Assuredly, I will return more frequently, akin to I have almost constantly, provided you maintain this climb.

Thank you for your thoughtful feedback! I’m delighted to hear you enjoyed the content. Your support and frequent visits mean a lot. I’ll continue striving to deliver quality posts.

Hi my loved one I wish to say that this post is amazing nice written and include approximately all vital infos Id like to peer more posts like this

Thank you for your lovely comment! I’m glad you found the post informative and well-written. I’ll be sure to share more content like this in the future.

I do not even know how I ended up here but I thought this post was great I dont know who you are but definitely youre going to a famous blogger if you arent already Cheers.

Thank you for your wonderful comment! I’m glad you enjoyed the post. Your encouragement means a lot to me. Cheers!

This webpage is phenomenal. The brilliant data reveals the proprietor’s interest. I’m awestruck and expect further such astounding sections.

Thank you so much for your kind words! I’m thrilled to hear that you enjoyed the content. Stay tuned for more exciting posts!